In the guitar effects industry, players often use subjective words like glassy, bell-like, or woody. From a physics standpoint, these terms are descriptors for harmonic presence. Which means that when a player pays for a boutique pedal, they are essentially purchasing a specific mathematical recipe of overtones. To understand why one pedal sounds like a chainsaw and another sounds like a violin, we must look at the physics of the harmonic series.

The Harmonic Series: The Anatomy of a Note

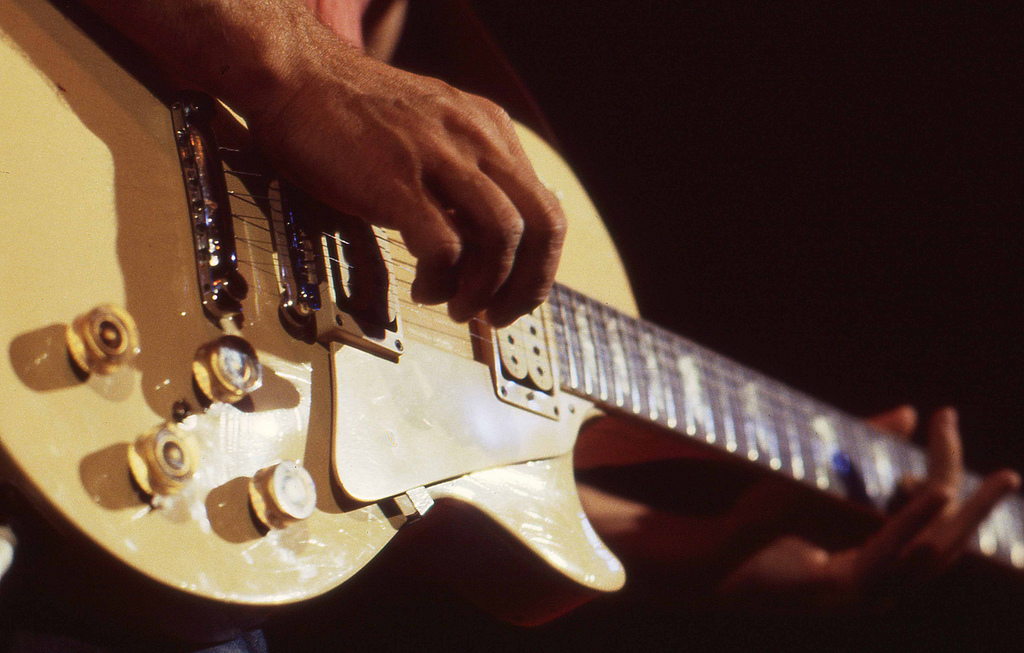

A guitar string is a physical resonator. When you pluck the Low A string (A₂), it oscillates at a fundamental frequency (f) of 110 Hz. However, physics dictates that the string cannot vibrate as a single, uniform entity. It simultaneously vibrates in integer multiples of that fundamental (220 Hz, 330 Hz, 440 Hz...), creating a series of overtones.

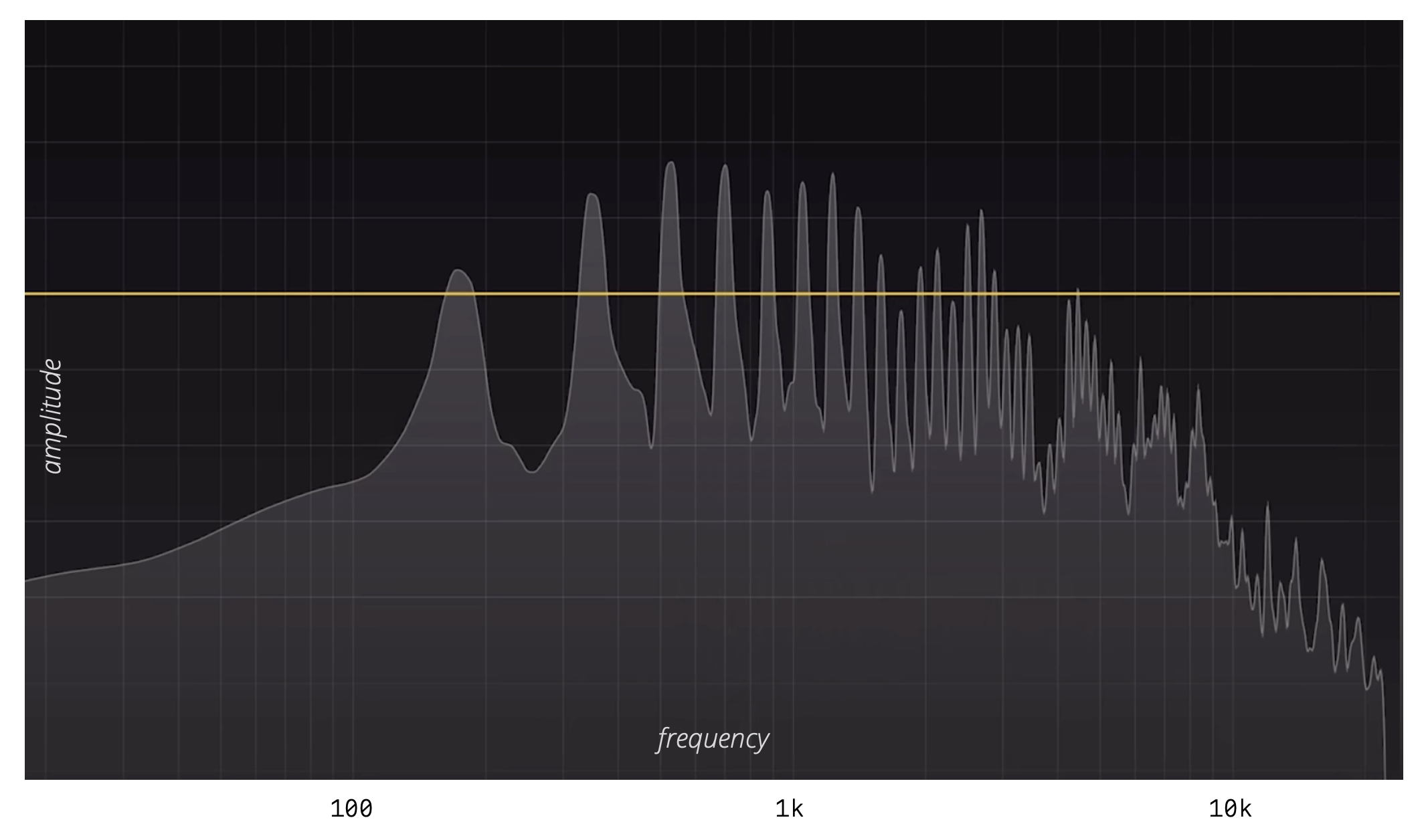

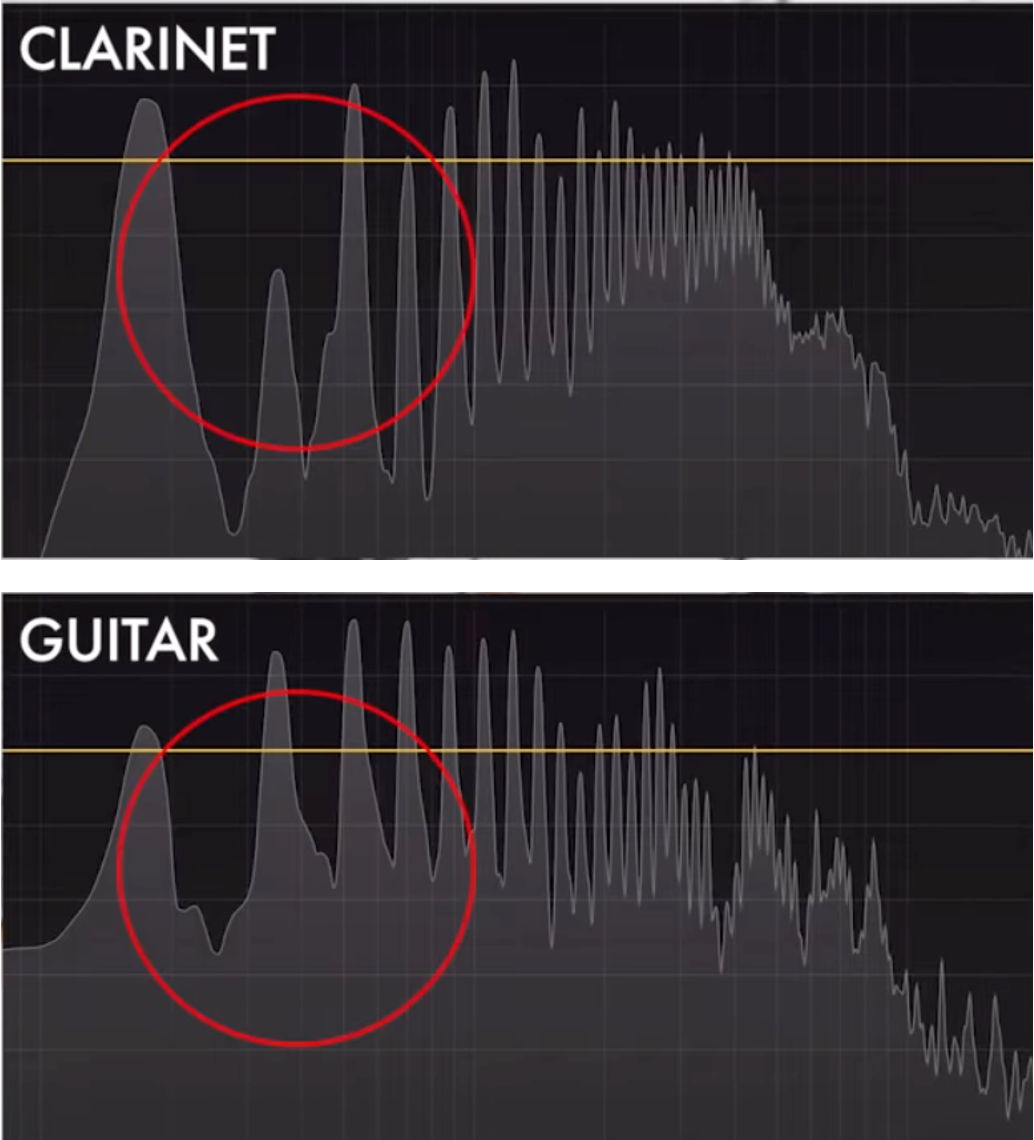

When you look at the frequency response of a single note on a guitar string, you can see just how much harmonic content there is. Every large peak you see is a harmonic. The fundamental frequency is clearly visible on the left, but the 2nd and 3rd harmonics are often louder than the fundamental itself. In this example, several harmonics exceed the amplitude of the fundamental.

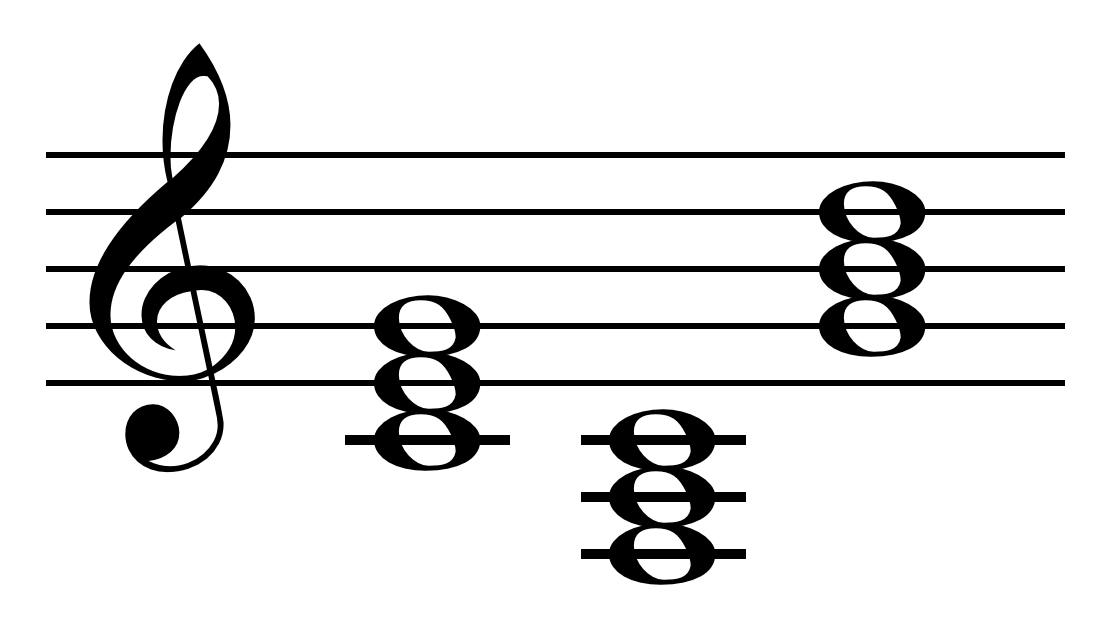

This series is infinite (1f, 2f, 3f... nf), but the relative volume (amplitude) of each multiple determines the specific character of your tone. The first few harmonics are the most important because they form the musical foundation of the "Major Chord":

The Recipe for Tone

The "recipe" for a specific tone is determined by the amplitude (volume) of each of these harmonics. In fact, if you were to listen to only the fundamental frequency of various instruments playing the same note, they would all sound the exact same. Whether it is a guitar, a piano, or a saxophone, the fundamental is simply a characterless sine wave. Timbre is the specific distribution of harmonic amplitudes that gives each instrument its unique voice.

The Major Chord and the Bluesy Seventh

The reason we find the harmonic series so pleasing is that the first six harmonics contain only three distinct notes: the Root, the 3rd, and the 5th. Together, these define the Major Triad. When you hear a single note on a guitar, your brain is actually processing a naturally occurring major chord, which is pleasing to the ear.

The 7th harmonic (7f) is where the "grit" begins. In music theory, this frequency is notably flatter than a standard minor 7th on the musical scale. This specific "out of tune" quality shifts the Major Triad into a Dominant 7th chord. This "Harmonic Seventh" is responsible for the bluesy growl and raw character we associate with vintage rock tones. It is the first point in the series where the math introduces tension and complexity.

Why Higher Harmonics Sound "Harsh"

As the series continues beyond the 7th harmonic, the intervals become increasingly smaller and more dissonant. In a glassy, bell-like, or vibrant tone, the lower-order harmonics (2 through 7) are preserved or enhanced. Conversely, a "harsh" or "fizzy" tone is often the result of too much energy in much higher, dissonant harmonics like the 9th, 11th, or 13th.

Position Matters: Fretting and Picking

The specific distribution of harmonics on a guitar is not fixed. It changes dramatically based on two factors: where you fret the note and where you pick the string. Understanding both is key to shaping your tone before it ever hits a pedal.

Where You Fret (Left Hand)

The same pitch played at different positions on the neck will have a different harmonic profile. An open A string and an A fretted at the 5th fret of the low E string are the same fundamental frequency, but they sound noticeably different.

When you fret a note higher up the neck, you shorten the vibrating length of the string. A shorter string has a different stiffness-to-length ratio, which subtly alters how the upper harmonics behave. Additionally, your fretting position changes where you are relative to the pickups. At the 12th fret, you are closer to the neck pickup than when playing open strings or in the first position.

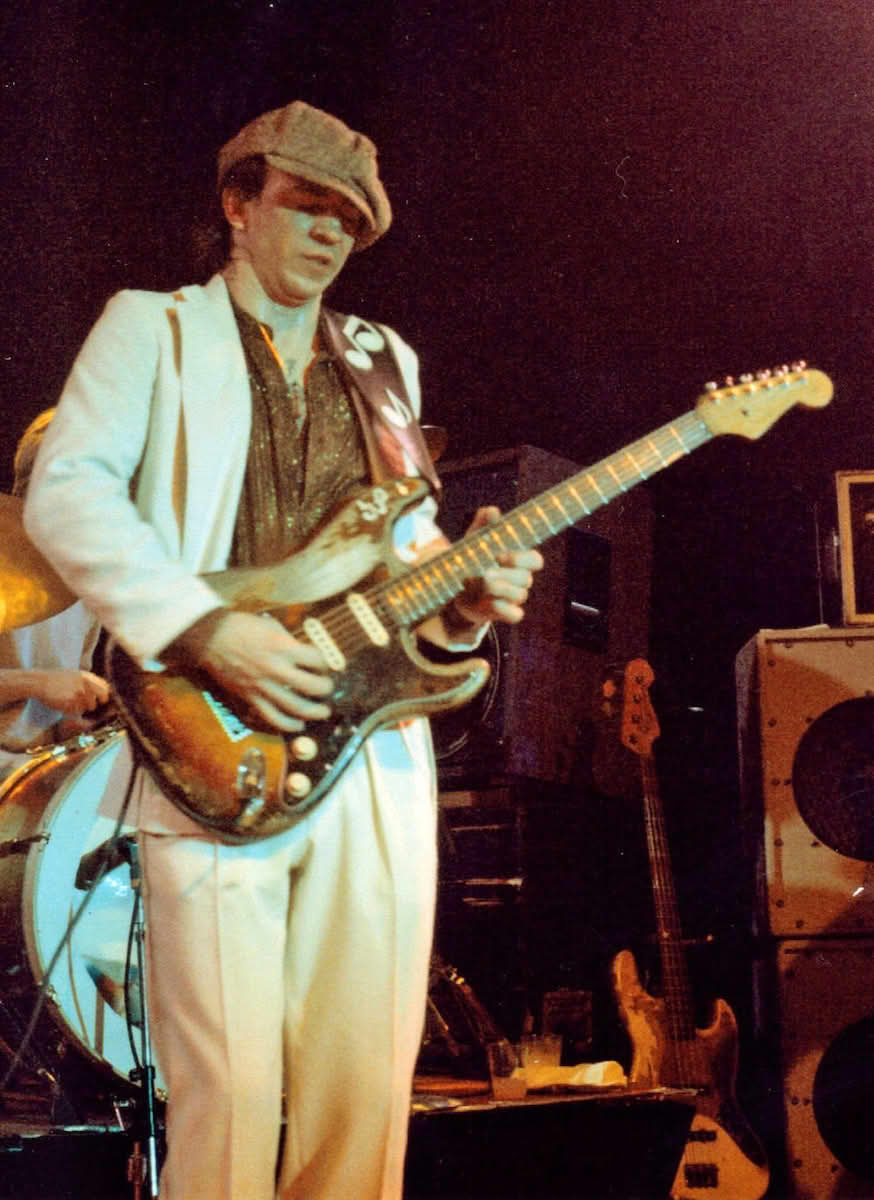

The SRV Tone

Stevie Ray Vaughan was famous for his thick, vocal lead tone, which he often achieved by playing melodies high up on the neck around the 12th fret. This position produces a warmer, thicker sound because the shortened string emphasizes lower-order harmonics, and the fretting hand is positioned closer to the neck pickup. Combined with his heavy string gauge and aggressive vibrato, this created his signature "singing" lead sound.

Where You Pick (Right Hand)

When you pick a string, you create a displacement at that exact point. Any harmonic that has a node (a point of zero movement) at your picking location will be suppressed. Conversely, harmonics with an anti-node (a point of maximum movement) at that location will be emphasized.

Picking Near the Bridge

Picking close to the bridge excites higher-order harmonics because the lower harmonics have nodes near the string's endpoints. This produces the bright, cutting, "trebly" tone favored for lead lines and articulate rhythms.

Picking Near the Neck

Picking over the neck (or near the 12th fret) emphasizes the fundamental and lower harmonics while suppressing the higher ones. This creates a warmer, rounder, more "mellow" tone often used in jazz and ballads.

This principle is why classical guitarists and jazz players obsess over right-hand position. The same note, on the same string, with the same fretting hand, can have a completely different timbre based solely on pick placement. Your picking hand is essentially a real-time EQ.

Physical Constraints: Why a Clarinet Sounds "Hollow"

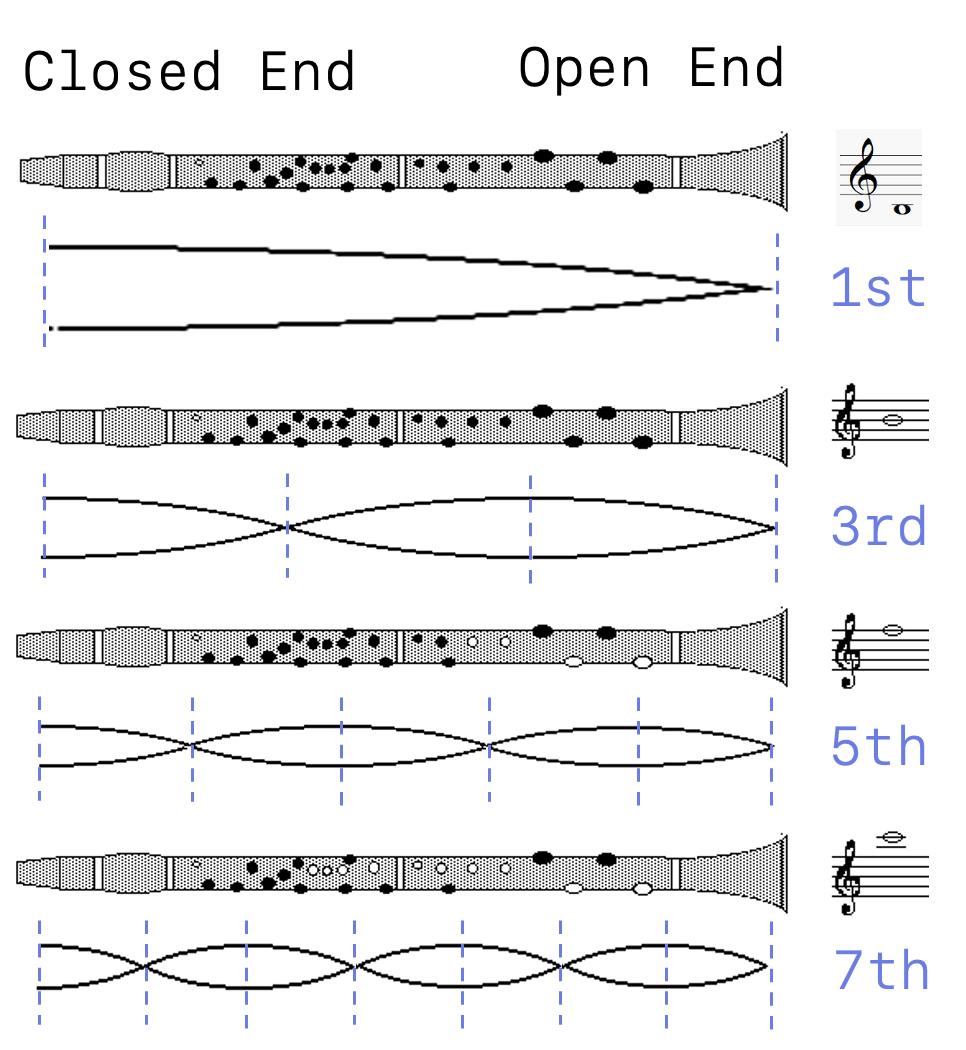

The harmonic profile of an instrument is dictated by its physical boundaries. A guitar string is fixed at both ends (the nut and the bridge), which allows it to support both even and odd harmonics.

Conversely, a clarinet behaves as a "closed-pipe" resonator. It is closed at the mouthpiece and open at the bell. Because of this specific physical constraint, the air column can only form standing waves that have a node at one end and an anti-node at the other. Mathematically, this physical limitation eliminates all even-numbered harmonics. A clarinet produces almost exclusively odd harmonics (1st, 3rd, 5th, etc.).

The Geometry of Tone: Square vs. Sawtooth Waves

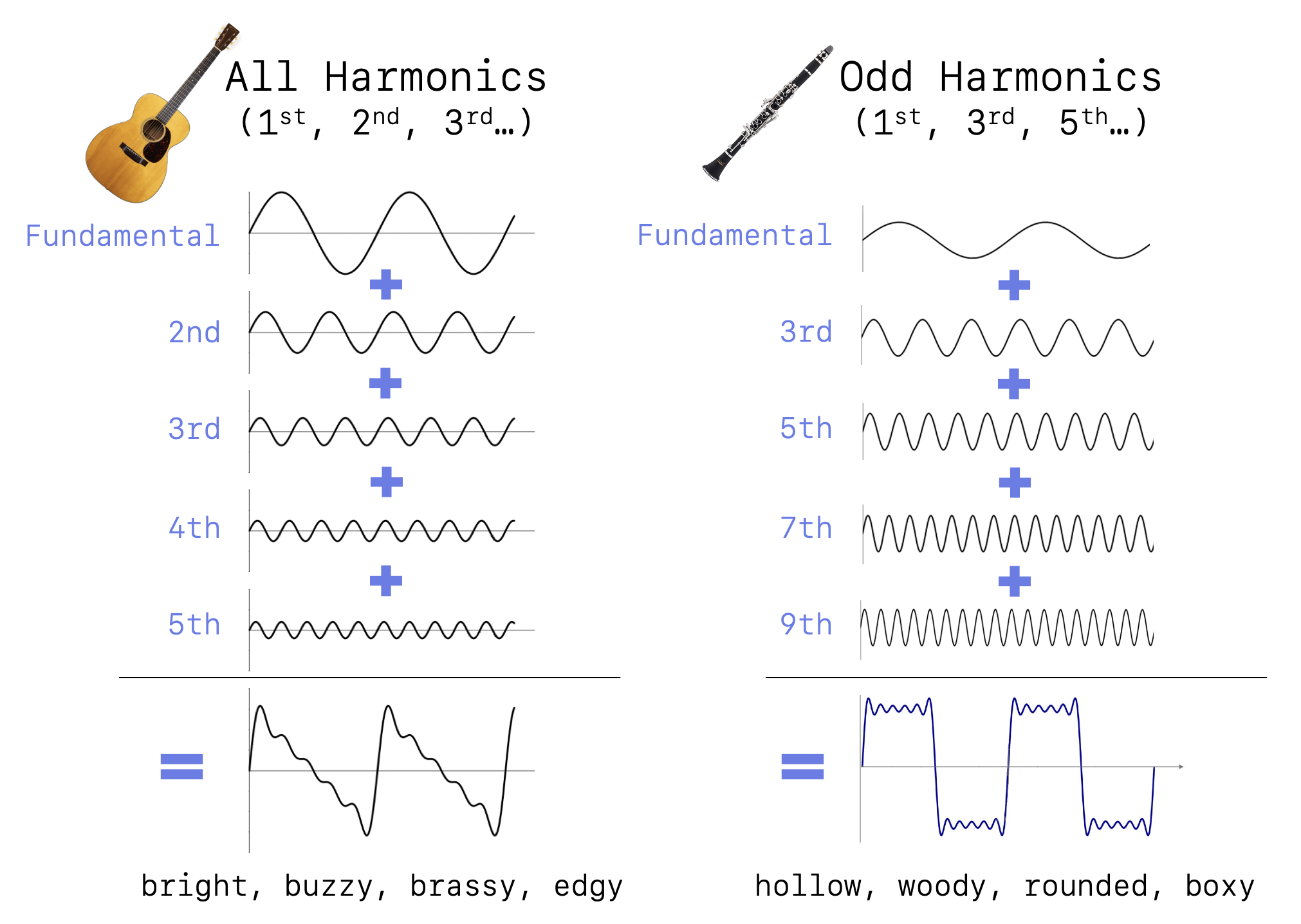

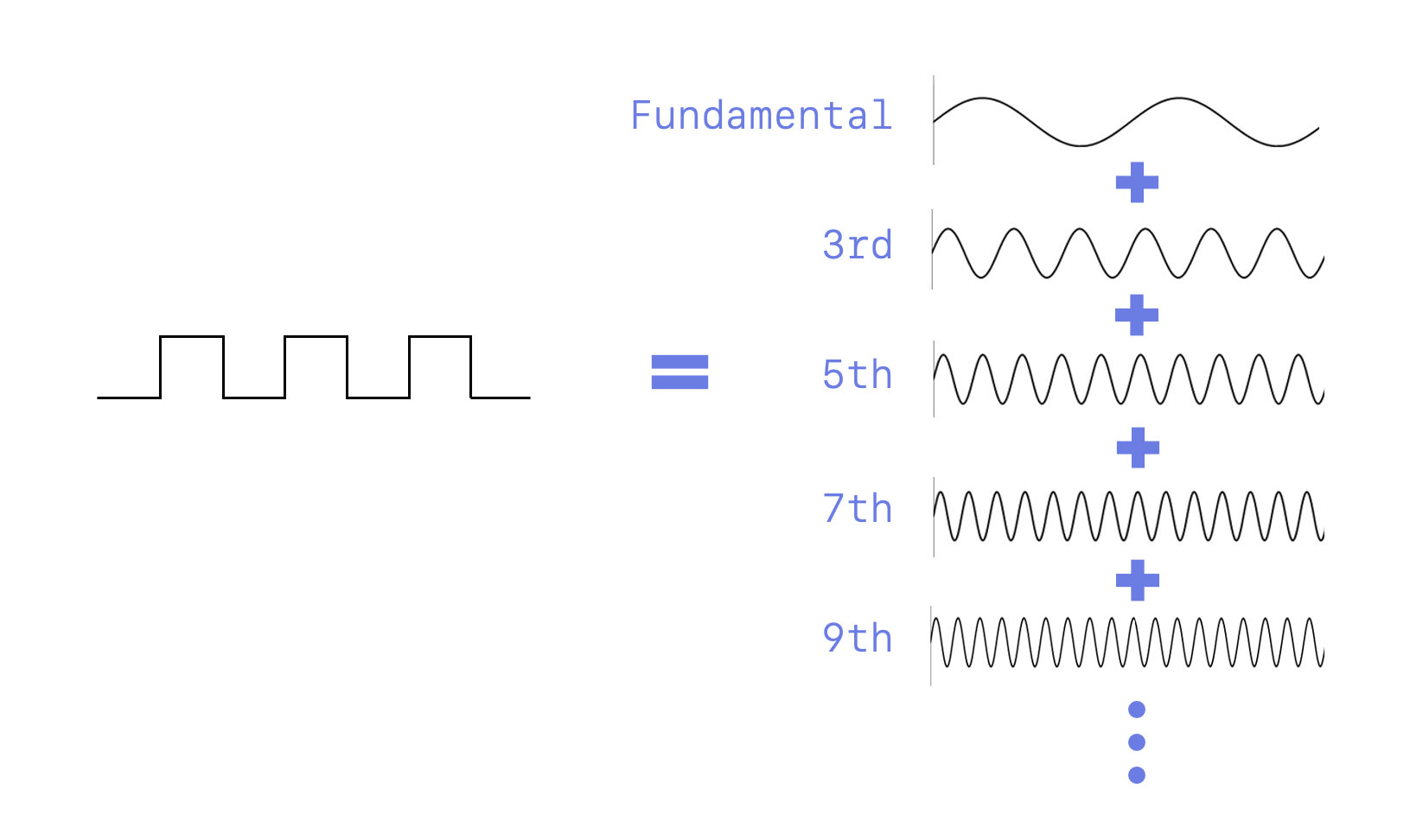

This brings us to the most important principle in signal shaping: the relationship between harmonic content and wave geometry. Through the lens of Fourier analysis, we know that complex wave shapes are built from simple sine waves.

Sawtooth Waves (All Harmonics)

If you include every harmonic in the series (both even and odd), the wave takes on a jagged, ramp-like shape known as a sawtooth wave. These are associated with bright, buzzy, and brassy tones.

Square Waves (Odd Harmonics Only)

If you take a fundamental sine wave and add only its odd-numbered harmonics (3rd, 5th, 7th, and so on), the wave begins to flatten out. Eventually, it becomes a square wave. This explains why the clarinet, which lacks even harmonics, produces a wave that is essentially a rounded square wave. These are the "hollow," "woody," or "boxy" sounds.

When we use clipping diodes to "chop off" the peaks of a sine wave, we are reshaping the signal toward these geometric forms.

Clipping and the Creation of Harmonics

The key insight is simple: when you clip a signal, you introduce harmonics. A pure sine wave contains only the fundamental frequency. But when you clip its peaks, you're forcing it toward a square or sawtooth shape, and that change in shape creates new harmonics that weren't present in the original clean signal.

This is what distortion actually is. A "high-gain" sound is simply a signal that has been so heavily clipped that it has become a harmonic-rich square or sawtooth wave. These added harmonics are what allow a distorted guitar to cut through a dense mix.

In a clean signal, the fundamental might be the strongest, but as we introduce clipping, we shift that energy. A glassy or bell-like tone has a specific emphasis on higher-order even harmonics, while a woody or vocal tone might emphasize a different cluster. The unique fingerprint of an instrument or a pedal is simply the specific distribution of these amplitudes across the spectrum.

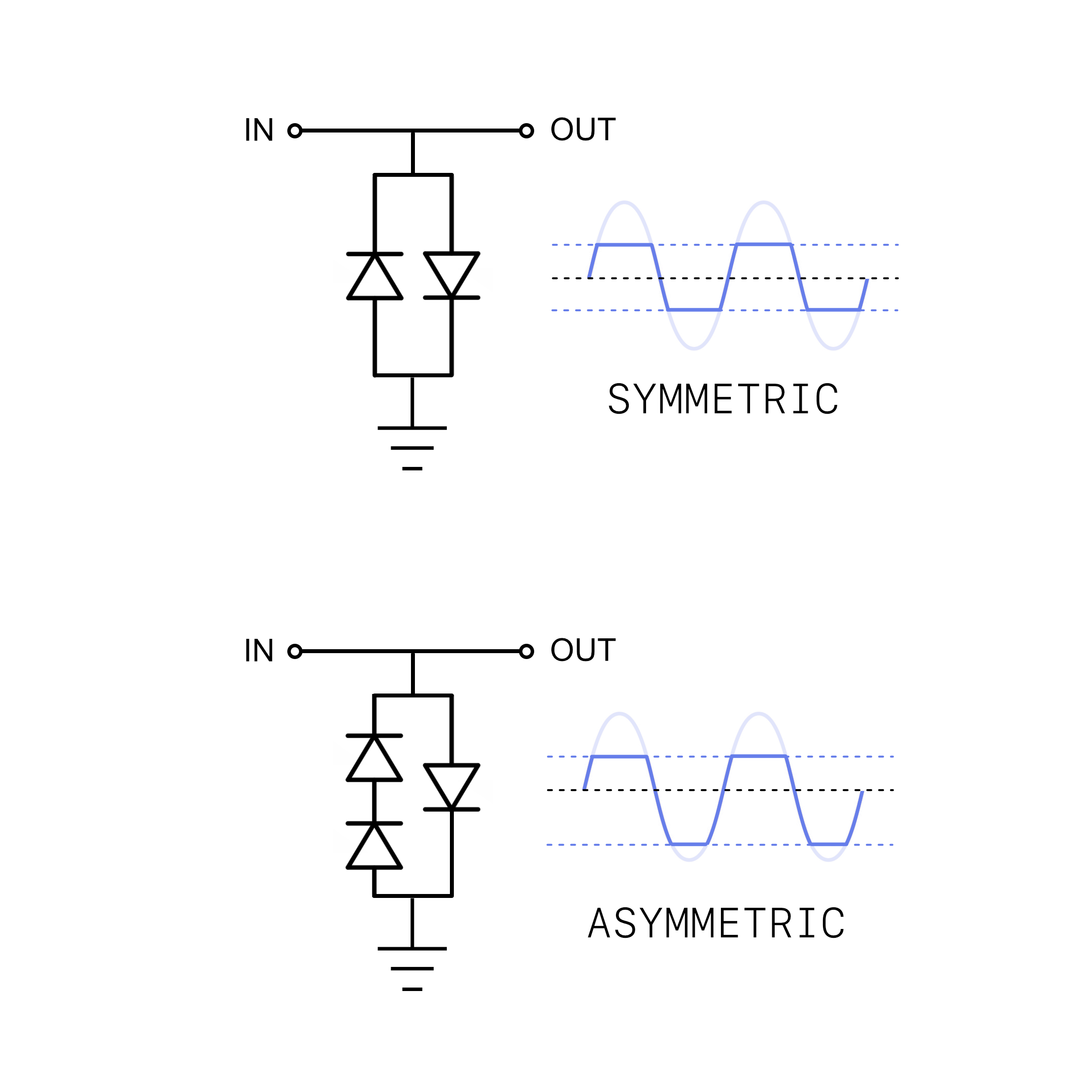

Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical Clipping

The designer's choice of clipping architecture determines which harmonics are introduced to the signal.

Symmetrical Clipping

The positive and negative peaks are clipped equally. This emphasizes odd-order harmonics. This results in the compressed, smooth, and mid-focused sound characteristic of "Tube Screamer" style circuits.

Asymmetrical Clipping

The wave is clipped harder on one side than the other. This introduces even-order harmonics. Since even harmonics are octaves, our ears perceive this as "musical" or "warm." This mimics the natural, non-linear behavior of vacuum tubes.

Psychoacoustics: The Missing Fundamental

The human ear is a highly specialized frequency analyzer. There is a phenomenon known as the "Missing Fundamental" where, if the 2nd and 3rd harmonics are strong enough, our brain will "hear" the fundamental frequency even if it is physically absent. This explains why a small practice amp speaker can still sound "deep." The speaker outputs the harmonics, and your brain does the rest of the math to fill in the bottom end.

Conclusion: Engineering Tone

Every knob you turn, every pedal you choose, and every position you pick on the neck is shaping the harmonic content of your signal. The subjective language we use to describe tone (warm, glassy, harsh, fat) maps directly to the physics of which harmonics are present and at what amplitude.

Once you understand that distortion is the creation of new harmonics, and that different clipping architectures emphasize different parts of the series, you can stop chasing "magic" and start making informed decisions about your sound. The mystery becomes mathematics.